When AI Starts Writing Code, Humans Start Reading Code

Max Kanat-Alexander, a Developer Experience expert at Capital One, said something in a talk: "Writing code has become reading code." On the surface, this is a description of workflow changes. In reality, it reveals a power shift happening in software engineering.

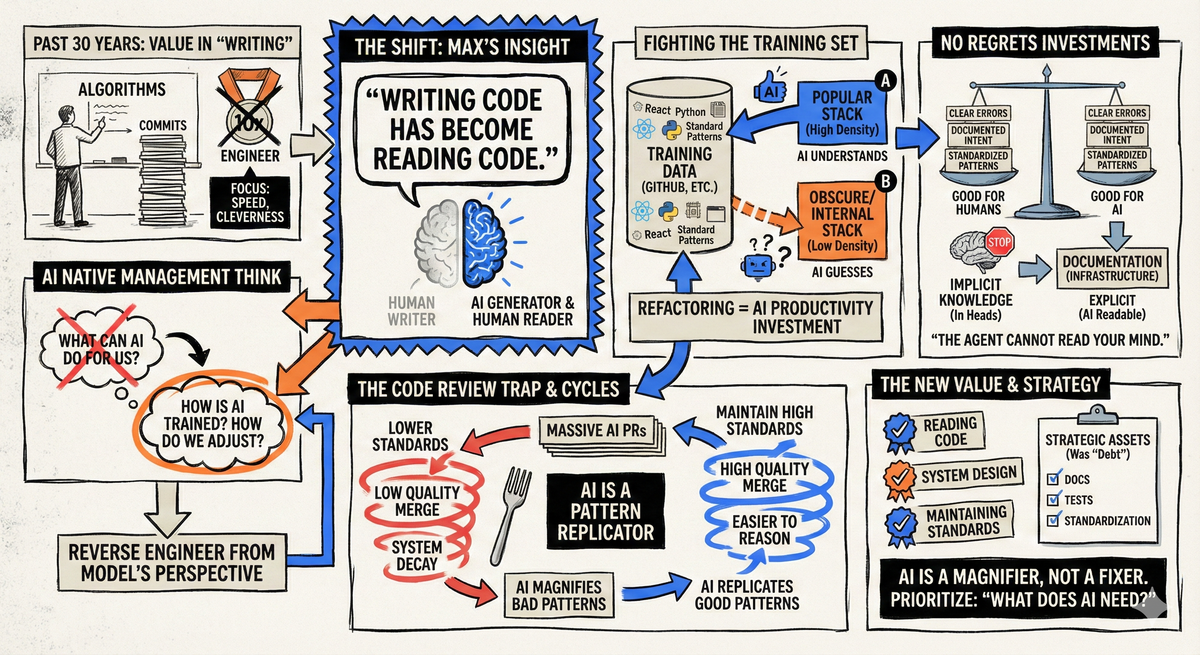

For the past thirty years, a programmer's value lay in "writing." Writing fast, writing clever, writing elegant. The entire industry built a complete culture around this action: from whiteboard algorithms in interviews, to commit counts in open source communities, to the myth of the "10x engineer." But the emergence of AI coding agents is uprooting this entire value system.

Max's talk didn't discuss how many engineers AI will replace, nor did it predict which technologies will win. He addressed a more pragmatic question: If AI agents are already working on your team, what kind of environment should you prepare for them?

The answer to this question points to an entirely new way of thinking about software engineering management.

I call this way of thinking AI Native software engineering management.

Its core logic is an inversion: instead of asking "what can AI do for us," it asks "how is AI designed and trained, and how should we adjust ourselves to maximize its utility." This is a framework that reasons backward from the model's perspective to organizational operations.

Max used a phrase in his talk that precisely captures this concept: "Fighting the training set."

Large language models derive their capabilities from the data they've seen. When your code looks like millions of projects on GitHub, AI understands it more accurately. When your code uses some internal framework that only your company uses, AI can only guess. Using obscure languages, custom package managers, non-standard architectural patterns—these choices in the past might have only increased the learning curve for new hires. Now they directly undermine AI agents' capabilities.

This means the logic of technology selection has changed.

In the past, considerations for choosing a tech stack were: what the team is familiar with, what solves the problem best, what talent is available in the hiring market. Now, you must add a new dimension: How dense is this technology's representation in the training set? React is easier for AI to understand than some niche frontend framework, not because React is better, but because React code appears millions of times in training data.

This is a wake-up call for teams carrying ten years of technical debt, and simultaneously an opportunity. Large-scale refactoring, or even large-scale rewrites, are no longer just "paying down debt"—they're prerequisite investments for capturing AI productivity gains. Those projects that migrate old internal frameworks to mainstream tech stacks, previously shelved because ROI was unclear, can now have their value recalculated: you're not just reducing maintenance costs, you're making your entire codebase readable to AI agents.

Max calls this type of investment "no-regrets investments." In an era of such dramatic technological change, CTOs are anxious that today's investments will be obsolete tomorrow. But Max believes there's a category of investments that won't become obsolete: improvements that make both humans and AI more productive.

This sounds like a truism, but from an AI Native perspective, its implications are deeper than they appear.

When you prepare a testing environment with clear error messages for AI agents, you're helping a system that cannot "intuit" problems to debug. When you document the "why" behind business logic, you're providing context for an agent that cannot attend meetings or read the assumptions in your head. When you refactor messy code into a reasonable structure, you're reducing the edge cases that a pattern-matching-dependent system needs to handle.

Max said: "The agent cannot read your mind. It did not attend your verbal meeting that had no transcript."

This statement highlights another dimension of AI Native management: organizational tacit knowledge must be made explicit. The architectural decision rationales that exist in senior engineers' heads, the "don't touch this" warnings passed down through word of mouth, the business logic explanations that only appeared in Slack conversations—none of these exist for AI agents. Documentation is no longer an optional virtue; it's the infrastructure that enables AI to work.

"What's good for humans is good for AI." That's Max's summary. But I want to flip this statement: When you start designing development environments from AI's needs, humans benefit too. This isn't coincidence—it's because AI's limitations—needing clear error messages, needing standardized patterns, needing documented intentions—happen to be the same limitations humans face when collaborating at scale.

The most tension-filled section of the talk was about code review.

Max described an imminent scenario: AI agents can generate massive numbers of Pull Requests in minutes. Where an engineer might have submitted five PRs a week in the past, now it might be fifty. Review workload explodes, but review capacity hasn't kept up.

Here a trap emerges. When PRs pile up like mountains, teams tend to lower review standards to merge code faster. But Max warns this triggers a vicious cycle: low-quality code makes systems harder to maintain, harder-to-maintain systems cause AI to produce more low-quality code, and eventually the entire system collapses.

Conversely, if teams can maintain high review standards, they enter a virtuous cycle: high-quality code makes systems easier to reason about, AI performs better in systems that are easier to reason about, and the code it produces is higher quality.

From an AI Native perspective, the key to this cycle lies in understanding AI agents' essential nature: they are powerful pattern replicators. When your codebase is full of quality patterns, AI replicates those patterns. When your codebase is full of expedient hacks and technical debt, AI faithfully replicates those problems too—at ten times the speed.

Max's talk reveals a larger trend.

The emergence of AI coding agents hasn't made software engineering simpler. It has shifted the core skills of software engineering. In the past, value lay in the ability to write code. Now, value is shifting toward the ability to read code, the ability to design systems, and the willpower to maintain quality standards.

For individual engineers, this means: time spent learning some niche framework may be less valuable than time spent understanding mainstream ecosystems and system design principles.

For organizations, this means: AI Native software engineering management requires you to re-examine your entire development process from the model's perspective. Is your tech stack's coverage in the training set high enough? Are your error messages clear enough for a system without intuition? Are your architectural decisions documented? Is your codebase full of good patterns AI will replicate, or bad patterns that will be amplified?

Those projects long viewed as "infrastructure debt"—documentation, testing, standardization, modernization—have suddenly become strategic assets. AI agents are not tools for solving technical debt; they are leverage that amplifies technical debt's consequences.

Max didn't offer an exciting vision of the future. He offered a to-do list. But this list's priorities need to be reordered with AI Native thinking: Don't ask "what do we want to do," ask "what does AI need so it can help us do more."